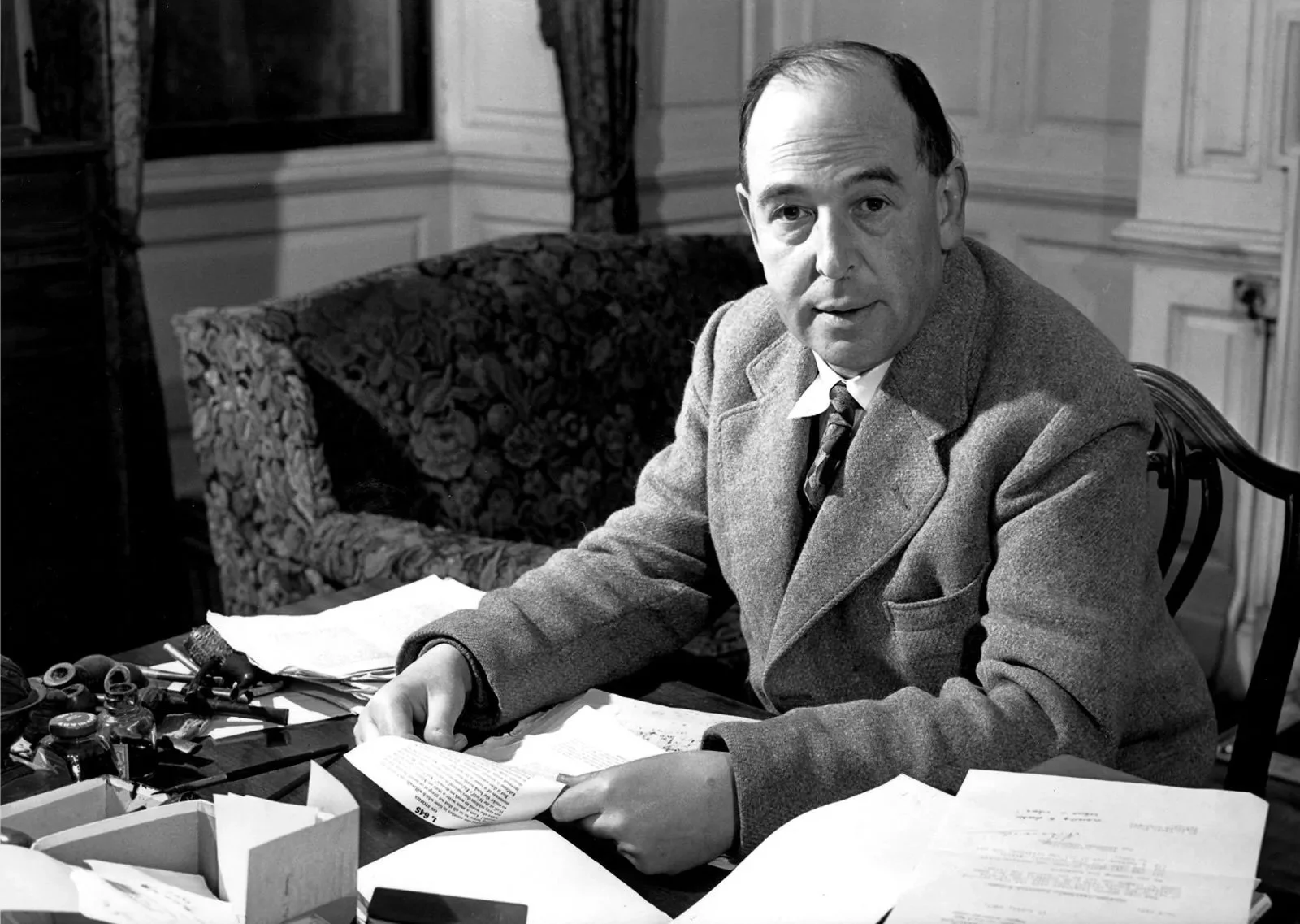

10 Reasons Why I Want to be Like C. S. Lewis

Even though I will never be half the man he was!

It’s almost cliche in the world of Christian thinkers to say “C. S. Lewis is my favorite author,” but I don’t care. He is my favorite author! He’s more than that, really, he is a kind of mentor to me. His writings have helped me in more ways than I can count. They have challenged my perspective, rebuked my sins, caused me to love Jesus more truly, caused me to love my neighbor better, and gave me a burning passion to connect the world to Jesus Christ and to classical education. I cannot enumerate all the ways in which C. S. Lewis has had a positive impact upon me, but I can give you at least ten reasons why I admire him and want to be more like him.

1) C. S. Lewis read an unfathomable number of books.

If you’ve read C. S. Lewis at all this should be obvious to you. Whether it is his fiction which makes constant allusions to stories of Greek and Roman mythology or whether it is his nonfiction where he directly references countless authors and works Lewis was clearly a voracious reader. Nowhere does this hit home better, however, than if you read his personal letters. I confess I have only read the first volume so far (which starts when he is about 8 years old and finishes right after his conversion around the age of 30), but that alone contains about 1,000 pages of personal letters. What struck me when reading those letters is that I couldn’t hope to catch the man in reading. By the time C. S. Lewis was about 18 years old he had probably read more books in English, French, German, Greek, and Latin than I’ll read in my whole life. I may never catch him, but I would like to make an honest effort. If you ever wonder what produced a man like C. S. Lewis, this is part of the equation.

2) C. S. Lewis wrote across many genres of literature.

As an aspiring author myself (hopefully aspiration will turn into publication eventually) I appreciate the diversity of Lewis’ writings. He has, of course, written the famous children’s fantasy series The Chronicles of Narnia, an absolutely brilliant work of Christian imagination, but he also has written so much more. He has science fiction in his Ransom Trilogy, he has rewritten mythology in ‘Til We Have Faces, he has written theology by mocking conversation between a young demon and his mentor in The Screwtape Letters, he took us on a bus trip out of hell in The Great Divorce, and he wrote an allegory of his own life and conversion in The Pilgrim’s Regress.

In addition to these various forms of brilliant fiction writing he was also a scholar who gave us incredible works of non-fiction. He taught us what education is really supposed to be about in The Abolition of Man, he explains the Medieval world to us in works like in The Discarded Image, and he tells us about the early world of English Literature in his Oxford’s History of English Literature in the Sixteenth Century (which he loving called his “O’Hel” book…or not otherwise not so lovingly). He was a fierce essay writer who addressed countless topics of literature, theology, philosophy, history, and apologetics and these can be seen in collections like God in the Dock, On Stories, and many others. You can even read a sermon written by C. S. Lewis in The Weight of Glory.

So many more works could be mentioned here, but Lewis had a knack of being able to tell us things worth hearing in just about any form you’d like to hear it.

3) C. S. Lewis boldly defended classical education.

Already mentioned above, The Abolition of Man was written to address the shift in education that Lewis was observing around him. What was that shift? It was the shift away from belief in the transcendentals of truth, goodness, and beauty as objective categories rather than mere personal emoting. It was the move towards experimental forms of training children as opposed to passing on truth, tradition, and civilization. Lewis saw clearly what few in his day could, he saw that what it means to be human was being stripped from the souls of boys and girls before they could possibly know what was being done to them.

Lewis didn’t just see it, he called it out. In Abolition of man he points to the glaring destruction coming our way if we leave the tried and true paths of classical education. Today we see the exact fallout he predicted. But Lewis did not only tell us this in his works of educational philosophy, he told us this story by introducing us to Eustace Clarence Scrubb (a name he almost deserved) in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader and by introducing us to Experiment House The Silver Chair. Indeed the N.I.C.E. of That Hideous Strength embodies the goals of modern education devoid of all that foolish sentiment.

C. S. Lewis told us the truth about the dangers of the shift away from classical education, he showed us what a real education should look like, and he modeled for us what an educated person should be.

4) C. S. Lewis boldly defended the Christian faith.

Mere Christianity is, perhaps, Lewis’ best known non-fiction work. Perhaps it is not as well known, however, that this book was transcribed and edited together from a series of radio broadcasts he made during World War 2 which were meant to encourage allied forces and to set their minds upon Christ as they fought against a great darkness. In this book Lewis makes his most straightforward case for what Christians believe and why everyone should be one. Written as a book for every man, his master use of the analogy (something he has in common with St. Athanasius) makes powerfully clear why Christianity is true and why it brings peace and purpose to all who embrace it.

Lewis’ apologetic works for Christianity is, in one sense, everything he wrote. His Christian mind permeated every matter he addressed. In God in the Dock we find a collection of short essays addressing different matters of import to the defense of the faith. In Miracles we get a whopper sized defense of the plausibility of Miracles over an against enlightenment rationalists like Hume who attempted to reject them altogether. The Problem of Pain is Lewis academic wrestling with the problem of evil and suffering and the goodness of God. Perhaps even more potently, Lewis addresses suffering when it touched him personally in A Grief Observed after losing his beloved wife, Joy, to cancer. Even in his beloved Narnia series we see the building blocks of apologetics as the Professor teaches the Pevensie children to think clearly about who is telling the truth, Lucy or Edmund.

At all times and in all ways, Lewis breathed out a robust case for the Christian faith. He gave apologetics for the truth of Christ and he made no apology for doing so. All these years later he remains a unique thinker whom many skeptics are willing to listen to when they won’t listen to anyone else.

5) C. S. Lewis was a fierce believer in close male friendship

In our world today most people assume if two men love each other they must be gay. They force this pathetic notion back upon great friendship of history and literature from David and Jonathan to Sam and Frodo. This plague of a notion is just one factor explaining why so many men today have so few real friendships, they fear being labeled. But in Lewis and Tolkien and Barfield (and others) we have a great example of fierce male friendship. Intellectual, joyous, and masculine, these gentlemen read great literature together, wrote great books together, walked the countryside together, argued together (both with each other and beside each other), smoked pipes together, had pints together, and loved Jesus together.

Those who cannot conceive Friendship as a substantive love but only as a disguise or elaboration of Eros betray the fact that they have never had a Friend. The rest of us know that though we can have erotic love and friendship for the same person yet in some ways nothing is less like a Friendship than a love-affair. Lovers are always talking to one another about their love; Friends hardly ever about their Friendship. Lovers are normally face to face, absorbed in each other; Friends, side by side, absorbed in some common interest. - The Four Loves

It was their Christianity that gave them their friendship. The Christian bond is that which can make men closer than brothers. Nothing could be less “gay” than men joyously and fearlessly laboring aside one another for the Kingdom of God as Lewis and his friends did. We need more men getting together and being there for one another, encouraging one another in their hard work for their God and for their wives and kids. Friendship is a blessing from the Lord which men should seek after with prayer.

“In friendship...we think we have chosen our peers. In reality a few years' difference in the dates of our births, a few more miles between certain houses, the choice of one university instead of another...the accident of a topic being raised or not raised at a first meeting--any of these chances might have kept us apart. But, for a Christian, there are, strictly speaking no chances. A secret master of ceremonies has been at work. Christ, who said to the disciples, "Ye have not chosen me, but I have chosen you," can truly say to every group of Christian friends, "Ye have not chosen one another but I have chosen you for one another." The friendship is not a reward for our discriminating and good taste in finding one another out. It is the instrument by which God reveals to each of us the beauties of others.” - The Four Loves

6) C. S. Lewis was a man who kept his word.

If you’ve gone to that next level of C. S. Lewis obsession (join me, won’t you?) and started reading numerous biographies (Alan Jacob’s The Narnian is my favorite) or if you’ve reached boss level and read his letters then you may know something about Mrs. Moore. Lewis, while preparing for the trenches of World War 1, made a pact with his friend Paddy Moore that if anything happened to one of them then the other would look after the remaining parent of his friend. Paddy died in that war and Lewis kept his word.

Now, admittedly, there is some reason to think that prior to Lewis’ conversion to the faith at about the age of 30 that something of an untoward relationship may have taken place between himself and the widowed Mrs. Moore. Though it is speculation it is not without some good evidence that some claim Lewis may have had an affair for a time with Janie Moore. What is certain, however, is that he took her into his home (which he shared with his brother) and cared for and provided for her. What is even more certain is that after he became a believer in Christ, he honored his word and cared for her in a godly manner until the end of her life. Even when doing so became very difficult and draining upon him emotionally and financially, Lewis cared for her until she died.

Whatever may have (or may not have) occurred between them when Lewis was in his early 20’s, his Christian service to an ailing widow demonstrated his faithfulness to a commitment he had made when was 18 years old. By the time Mrs. Moore passed away Lewis only had about 13 years left of his own life to live. He had remained unmarried (probably due to his unusual circumstances of caring for a woman in his home to whom he was not married). Though he did eventually marry his good friend Joy Davidman, Lewis sacrificed his youth to the care of his friend’s mother for many years. He acquitted himself with honor and integrity and showed himself to keep his promise though it became a very costly one in more ways than one.

7) C. S. Lewis repented well.

Though Lewis grew up in a believing home with Christian parents he abandoned the faith when he was 15. His mother died when he was 9 and his father, struggling to manage without her, sent his two sons (Warner was his brother’s name) to boarding school. Eventually Lewis was placed into the private tutorage of “The Great Knock,” that is to say William Kirkpatrick.1 He came and lived with “the Kirk” and his wife to finish out his pre-college education.

Those years were formative to Lewis in more ways than one. Lewis was sharpened significantly as a scholar during this time and the world has much to be thankful for in regard to Kirkpatrick’s influence. Lewis recounts his first interaction with Kirkpatrick in Surprised By Joy where he tells his reader that he had made an off-handed comment about being “was surprised at the “scenery” of Surrey” and that “it was much ‘wilder’” than he had expected. To which Kirkpatrick responded, “‘Stop! … What do you mean by wildness and what grounds had you for not expecting it?’” His demand for not speaking idle nonsense or making claims without justification was to Lewis “red beef and strong beer.” The demands for clarity, precision, and logic is part of what made the man so many of us love.

Even so, Knock was a pure rationalist and, like Hume, found the question of God meaningless. It was under his influence that Lewis abandoned the Christianity of his parents. He became a strict atheist and turned his heart away from the stories and fantasies he had loved in his youth to pursue more “serious” stuff that adults are supposed to care about. During this 15 year period Lewis’ imagination, like his soul, was dead. In one of his letters to Arthur Greaves, one of his oldest and longest lasting friendships, he admitted this point that the imagination he had enjoyed so much as a child had abandoned him (see Boxen to get an idea of his earliest childhood creations). It was only his love for George MacDonald (particularly Phantastes) and Norse Mythology that tethered him to any enjoyment of the fantastic.

It was, in fact, that love of Norsemen that brought him into contact with J. R. R. Tolkien who was running an Icelandic languages club at Oxford. Over time Lewis’ friendship with him and Owen Barfield began to wear down his arguments against the Christian faith he had abandoned. He realized, to his great chagrin, that his arguments weren’t very good after all. He recounts the day he gave up his battle against God:

“You must picture me alone in that room in Magdalen, night after night, feeling, whenever my mind lifted even for a second from my work, the steady, unrelenting approach of Him whom I so earnestly desired not to meet. That which I greatly feared had at last come upon me. In the Trinity Term of 1929 I gave in, and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England. I did not then see what is now the most shining and obvious thing; the Divine humility which will accept a convert even on such terms. The Prodigal Son at least walked home on his own feet. But who can duly adore that Love which will open the high gates to a prodigal who is brought in kicking, struggling, resentful, and darting his eyes in every direction for a chance of escape? The words “compelle intrare,” compel them to come in, have been so abused be wicked men that we shudder at them; but, properly understood, they plumb the depth of the Divine mercy. The hardness of God is kinder than the softness of men, and His compulsion is our liberation.”

Lewis repented well. He acknowledged what was true even though he didn’t want it to be true. Once he admitted that Christianity was true it was then that he became one of its most powerful spokesmen. Lewis didn’t let his past sins and arrogance against God hinder him from putting all his energy into then promoting the truth of Christ which he had formerly flouted. He repented well because he repented completely. May it be said of us also that we believed what was true and not what we simply wanted to be true and that we acted according to the truth.

8) C. S. Lewis knew how to speak to the heights of academia.

Lewis was never “Dr. Lewis” but that should not give us a moment’s hesitation in recognizing his superiority to the majority of Ph.D.s of our own day. The world of education has changed a lot since his time and none for the better. Regardless, Lewis was able to write as an academic to academics, using all the right jargon and technical language, making use of the appropriate language of Latin, Greek, French, or German as needed. That’s far more than I can boast; he outstrips me at every turn (and I have a Ph.D.).

As mentioned above he wrote the Oxford History of English Literature in the Sixteenth Century (Excluding Drama) which is still being used in colleges today (at least the few good ones left). His works The Discarded Image, An Experiment in Criticism, and Studies in Words are excellent examples of Lewis’ academic and professional work. He was recognized in his own time as a scholar’s scholar though his Christianity and refusal to shut up about it (and also his non-academic forays into fantasy and sci-fi) made some of his fellow scholars turn up their nose at him and possibly cost him the Department Chair he deserved at Oxford. But, not to worry, Cambridge was happy to offer him the post he was due.

He was a force to be reckoned with and was by no means inferior to the best of scholars in his day (and miles beyond most in our own).

9) C. S. Lewis knew how to address blue-collar workers.

Despite the fact that Lewis could shake the ivory towers with his rigor and intellect, he could also talk to your average Joe just fine. As mentioned above, Mere Christianity was broadcasted and then rewritten to reach your average person and it succeeded (and continues to succeed). But Lewis did more than that, he wrote into the local paper at times to address local matters of politics and culture and he was several times asked to speak to local worker’s unions.

The fact that he wrote popular fiction like The Great Divorce and the Space Trilogy showed his ability to talk about big ideas in a way that was accessible and interesting to everyone. I suspect that part of the reason some of his fellows at Oxford disliked his writing popular works of fiction had something to do with jealousy. Most academics are only understandable by a few people in their own field and nobody reads what they write. Lewis did not have this problem.

10) C. S. Lewis knew how to tell stories to children.

Last, but far from least, Lewis could speak to the hearts of children. Few books can make children delight in wonder like The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe and its following stories. A magical entry into a magical world in the most common of places, mythical creatures come to life and in subjection to the great lion Aslan, and dark forces defeated by love and self sacrifice. Lewis knew how to write a faerie story! No, not a “fairy tale,” a “faerie story!” A story where magic is all around us unseen until one day it swallows us whole. Through that medium Lewis baptized countless imaginations to think about our world as they ought, a magical place with angels and demons, dragons and knights, good and evil, and God who cares to draw near to us and call us by our name so that we might learn to know him by his.

The sheer range of C. S. Lewis is awe-inspiring. I very much want to be like my mentor. How about you? Who has impacted you like this?

The above article was originally published on Study the Great Books. It is republished here with permission.