Four Protestants Who Built Classical Education

In the world of Classical Christian Education, there is an important resource that needs to be recovered: Protestant educators. We have a profound debt to pay to our Protestant fathers who built classical education for the last four hundred years. If we ignore them, then we will fail to recover the true powerhouse in classical education.

A prime example of how we have forgotten these important figures is a recent book on classical education which collected various selections from across the centuries, from Plato to T.S Eliot. While the book is a profound resource to classical educators, it is striking that it lacks almost all of the key Protestant figures who built classical education over the last few centuries. The editor includes selections from obvious Protestants like John Calvin and John Milton, but nothing by other prominent Protestant educators. This is not to cast aspersions on the editor as this error represents all of us.

In an effort to begin to rectify this problem, I offer four key Protestants who were crucial in building classical education: Cotton Mather, pastor and scholar, John Witherspoon, President of Princeton College, Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, the most important classicist of the modern era, and J. Gresham Machen, churchman and Greek scholar. I hope this brief introduction to these important men will reveal the riches that they hold for us if we study them.

Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (1663-1728) lived in Boston, Massachusetts, and was a pastor, doctor, scientist, and liberal arts master. He was educated as a young man at the Boston Latin School under the instruction of Ezekiel Cheever. Cheever’s instruction in classical education prepared Mather for the entrance examination at Harvard. At that time, the entrance exam for Harvard required students to translate Latin passages from Virgil and Cicero as well as be able to read through Greek passages from the Bible and Xenophon. Mather passed that exam at age eleven (1).

For Mather, the most important part of classical education was reading and knowing the Scriptures. He admonished families, “Before all, and above all, ‘tis the knowledge of the Christian religion that parents are to teach their children” (2). Mather himself tutored students from Harvard in Hebrew, reading aloud with them the Hebrew Scriptures (3). His work in educating the next generation included a meeting with a young Benjamin Franklin. One scholar summarizes Mather’s educational mission as “Through Christ all things become best known” (4).

Mather’s desire to know Christ drove his love for Latin and Greek and reading various authors. One scholar says, “Cotton viewed his bookshelves as a heavenly choir supporting the primary revelation of the Bible on his desk” (5). Mather taught that all knowledge rightly known reflects God and harmonizes with God’s word. He praised Harvard President Charles Chauncy not only for “‘how constantly he expounded the Scriptures to them in the college hall’ but also ‘how learnedly he…conveyed all the liberal arts unto those that sat at his feet’” (6). Leland Ryken adds, “One authority describes the initial tradition of Harvard as one in which ‘there was no distinction between a liberal and a theological education, and its two sources were first, Calvinism, and second, Aristotle’” (7). Through his work as a pastor, scientist, and classical educator, Mather’s goal was to teach students how to “make prayers out of what they read” (8).

John Witherspoon

John Witherspoon (1723-1794) famous for signing the Declaration of Independence and helping ratify the US Constitution, was president at the College of New Jersey which would later become Princeton. He was a classical educator, accomplished in Latin. He would write letters in Latin to one of his sons.

The Princeton curriculum like Harvard’s program was a classical curriculum. One historian says, “Like other colonial colleges in those days, much of Princeton’s curriculum, especially in the freshmen and sophomore years, centered on the intensive study of ancient Greek and Latin literature in the original languages” (9).

In 1771 Witherspoon started having students compete in speech contests in English, Latin, and Greek. These contests happened the day before Commencement. Any student in the college could compete for prizes. Many of the speeches focused on current political controversies.

By 1772, Witherspoon himself was teaching not only divinity and moral philosophy but history and rhetoric. One historian says, “ When published after his death, his Lectures on Eloquence had the distinction of becoming…the first American treatise on rhetoric” (10).

Witherspoon, like Cotton Mather, did not see any conflict between reason and biblical revelation. He said, “If the Scripture is true, the discoveries of reason cannot be contrary to it; and therefore, it has nothing to fear from that quarter” (11). His inaugural address as president at Princeton was entitled On the Unity of Piety and Science.

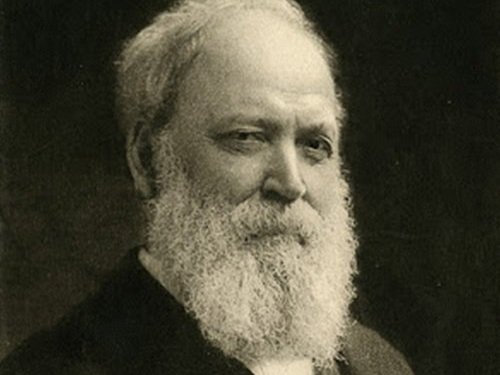

Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve

Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve (1831-1924) was a professor at the University of Virginia for twenty years before he was invited to work at Johns Hopkins University. (12) Gildersleeve was called “the greatest of American Hellenists” and America’s “foremost scholar” (13).

Gildersleeve was particularly interested in the Greek language and studied the various texts from Pindar to the New Testament to other early Christian authors. He also edited a version of Justin Martyr’s Apologies. One historian writes, “…Gildersleeve easily stood out as one of the real giants in American university education and second to none in the history of American classical scholarship” (14).

Gildersleeve composed his dissertation in Latin on the Neo-Platonist Porphyry. After the Civil War, he wrote an essay titled “A Southerner in the Peloponnesian War” which compared the American war to the ancient war between Athens and Sparta. He wrote several books on Latin syntax and grammar and his books were the standard texts on Latin into the 20th century. He was also the founder of the American Journal of Philology.

Gildersleeve knew the importance of classical education, writing in his essay “Classics and Colleges”:

Not only, then, do the traditions of the classic nations encounter us at every turn…But they have marked out our course; they have dug out our channels of thought and action. We build on Greek lines of architecture; we march on Roman highways of law; we follow Greek and Roman patterns of political and social life. Not to understand these forces, these norms, is not to understand ourselves (15).

Gildersleeve’s work as a Greek and Latin scholar propelled classical education forward into the twentieth century.

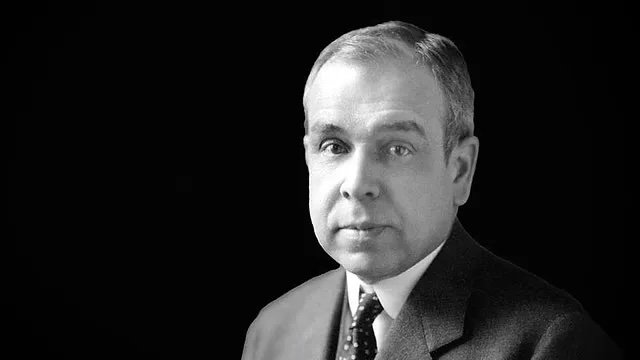

J. Gresham Machen

J. Gresham Machen (1881-1937), who studied under Gildersleeve, played a key role in combating liberalism and also furthered the work of classical education. In his most famous book, Christianity and Liberalism, Machen noted the deleterious work of Dewey and other modern educators, lamenting the way they were destroying classical education in schools. He was particularly concerned about laws trying to restrict education to only the English language which would undermine the study of classical languages. Machen was an avid lover of these languages, especially Greek, and he knew how critical they are in teaching a classical education.

One part of Machen’s work to combat liberalism was to encourage Christians to build Christian schools, a project he calls “the most important thing of all” (16). He describes the urgent need for this work:

An outstanding fact of recent Church history is the appalling growth of ignorance in the Church…The development is due partly to the general decline of education—at least so far as literature and history are concerned. The schools of the present day are being ruined by the absurd notion that education should follow the line of least resistance, and that something can be ‘drawn out’ of the mind before anything is put in (17).

Here Machen is commenting on the erroneous policies of Dewey and his followers. Machen rightly saw that this modern model would gut the education system, promoting ignorance rather than knowledge.

Machen fought back against these erroneous systems in two ways. First, under the influence of Gildersleeve’s scholarly example, Machen wrote a book on biblical Greek grammar. This textbook was an important resource for seminaries and schools in the 20th century. The second way Machen fought was in building a new college that was faithful to its Christian and Reformed roots. In 1929, he and several other Presbyterian educators started Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia (18). One of the first professors at the seminary was the famous Cornelius Van Til who had a student named Francis Schaeffer (19). Schaeffer is known for his work in fighting postmodernist philosophies of the twentieth century in his educational fellowship in Switzerland, called L’abri.

This quick summary does not do these four figures justice. There is much more that can and should be said about each of them. They have a great deal to offer us as we work to rebuild the legacy of classical education. Hopefully this brief introduction will promote further study and work. For those interested in other names, I recommend: John Amos Comenius, Isaac Watts, Jonathan Edwards, John Milton Gregory, and Abraham Kuyper. We can see that classical education has always been close to the heart of Protestants. In looking at these figures, we will find a rich theological and educational tradition that will help us build a robust classical education.

The First American Evangelical, Rick Kennedy, p 12.

Worldly Saints, Leland Ryken, p 162.

The First American Evangelical, p 2.

The First American Evangelical, p 13.

The First American Evangelical, p 3.

Worldly Saints, Ryken, p 164.

Worldly Saints, p 165.

The First American Evangelical, p 13.

https://www.acton.org/religion-liberty/volume-34-number-1/john-witherspoon-educating-liberty

https://www.acton.org/religion-liberty/volume-34-number-1/john-witherspoon-educating-liberty

https://www.acton.org/religion-liberty/volume-34-number-1/john-witherspoon-educating-liberty

Machen: Biography and Memoir, Ned Stonehouse, p 50.

Machen: Biography and Memoir, p 52-53.

Machen: Biography and Memoir, p 49.

Essays and Studies, Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve p 44-45.

Christianity and Liberalism, J. Gresham Machen, p 176.

Christianity and Liberalism, Machen, p 176.

Machen: Biography and Memoir, Stonehouse, p 447.

Francis Schaeffer: An Authentic Life, Colin Duriez, p 40.